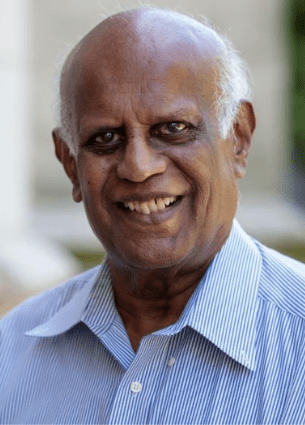

Interviewed by COSAS Chair, Constantine V. Nakassis, 9 April 2021.

Transcript of Interview:

Nakassis: So, I thought to get started, I wanted to ask you a little bit about how you came to the University of Chicago. You’ve had such an illustrious career. You’ve had positions across four continents: in India, of course, at the Central Institute of Languages, Indian Languages in Mysore, at Yale University, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, the Max Plank Institute, and the University of Melbourne. And you’ve worked in policy, in academia as a researcher, and as a pedagogue. But in many ways, as a professional academic, you began your career at the University of Chicago. And you came back to the University in the latter part of your career. So as a way to get started, I was hoping you could talk a little bit about how you came to the University of Chicago initially and then how you came back again more recently.

Annamalai: Thank you and COSAS for this opportunity to share my experience with Chicago University, which is very long, indeed! I did Masters in Tamil Language and Literature at Annamalai University. It was way back in 1960. After that when I taught Tamil at the University of Annamalai, linguistics came into the country as a new subject. So, I was attracted to it, and I got some training in the summers and then shifted my teaching to the new Linguistics Department. At that time, the opportunity came to teach Tamil at the University of Chicago. I grabbed it because I wanted to strengthen my linguistics training and the University of Chicago was a noted place for Chomskyian linguistics. So I made a condition that I should be allowed to be a student while I teach in the South Asian Department as a lecturer. This was in the year 1966, and it was just after my wedding, so it was kind of a wedding present to me and my wife! And then we arrived in Chicago in September 1966. I was here at that time for five years teaching Tamil. A. K. Ramanujan was there as my senior colleague, and also I completed my doctoral work in linguistics on a syntactic topic of Tamil. So in those days, it was just two years after the South Asian Studies became a separate department. So I could say that I was contributing to it from the early days. It included teaching of Tamil to students from various departments such as anthropology and political science and also the South Asian Studies. In addition to teaching, we needed to prepare instructional materials because as I said, the department was new and Tamil program was new, and therefore I was involved in preparing materials, which basically included the Jim and Raja conversations—which many, many people who learn Tamil in this country would be aware of—and also, with A. K. Ramanujan, a reference grammar of Tamil, which was not published, but it is usable for Tamil learners.

Nakassis: And the Jim and Raja conversations was written with James Lindholm.

Annamalai: Yes. James Lindholm was a friend of mine since his day in Madurai, India. And he was also a student in the Linguistics Department at that time, both as linguist and as friends we collaborated on creating that “Jim Raja “conversations.

Nakassis: Your advisor in linguistics was that James McCawley?

Annamalai: Yeah. The chair of my linguistics thesis committee was James McCawley. As you probably know, he didn’t know Tamil, but he was a scholar in Japanese, so he would bring some counterexamples from Japanese and apply to Tamil also; that was fascinating in some ways.

Nakassis: And what was the transition like going from doing a Tamil MA at Annamalai University to then getting PhD training at the University of Chicago?

Annamalai: I remember a major new experience for me was the way teaching takes place in Indian universities and in US universities, particularly in Chicago. My experience was (at Annamalai University) with my professor was T. P. Meenakshisundaram, who was a renowned scholar of Tamil and linguistics. The general pattern in Indian universities is that the professor is like a judge. He would deliver judgments, and we all would accept that. But the first experience I had with McCawley’s class was that he was more like an attorney, criticizing Chomsky. And that was a really revealing experience for me. In India, knowledge quoted in books is very much respected and not very much contested. So, when somebody criticizes Chomsky’s writing, for example, who was held to such reverence in my student days in India, it was a good experience. I think it still stays with me when I teach; I encourage students to question me about my views on Tamil.

Nakassis: And the other transition, of course, as you were teaching Tamil in India, and then you were also teaching when you came to do your PhD. As you said, you were also teaching through SALC Tamil language learners. Was that also a big transition to have a different kind of a Tamil student?

Annamalai: Yeah, it was a transition from teaching literature to college students to teaching Tamil as a second language here. One difference is teaching the spoken language which, as you know, is different from the literary language. That was not totally new, because in India I had some experience of teaching Peace Corp volunteers, who were coming to Tamil Nadu. So, I was exposed to the second-language teaching methodologies and also to the American students’ approach to education and language. So, in that way, it was not a new learning experience for me in the classes with the American students. In those days, the focus was on spoken Tamil for two reasons. One is that most of my students were from departments which required fieldwork for their research, so they wanted to master the way Tamil is spoken. And the second reason is that in those days—that is, in the sixties—there were no heritage students, students coming from Tamil family background who now want to have more of reading and writing Tamil rather than speaking, which they are somewhat familiar—at least they are familiar with listening. And one more reason is that the students who are specializing in South Asian texts were very few. So, most of my students who are either from anthropology or political science. So the task for me then was to write materials in colloquial Tamil, for which it was a practice—not only in Chicago but in most universities in this country—to use the Roman letters or Phonetic transcriptions for writing colloquial Tamil, because there is no standard spelling for writing the colloquial Tamil. So, the early materials would be including the Jim and Raja conversations would be in Roman script. Obviously, that has certain pedagogical impediments with reference to pronunciation and things like that. So when I came the second time, I converted those materials into Tamil script; and I had to develop a spelling system for colloquial Tamil, which I did at the second time. So this is a big transfer in the way spoken Tamil is taught as a second language to foreign students.

Nakassis: Oftentimes second language pedagogy and teaching is not housed in Linguistics Department. And so people who are trained in linguistics are not necessarily doing, as a parallel track, second-language teaching. I’m curious about how studying a PhD at the same time and teaching students from across the University, if you feel that that had an impact on your approach to how you see language?

Annamalai: That’s very true. Particularly the Chicago Linguistics Department, at that time, was focused on syntactic theory based on the Chomskyian model. There were not even courses in Applied Linguistics or Sociolinguistics. So, when it went back to Mysore to work in the Central Institute of Indian Languages, my focus had to shift from syntax to social issues with language and language education. But that’s a different story. Here, as you said, there was no specific training about second-language teaching in the Linguistics Department. But I had some training at Annamalai University in second-language teaching. But mostly it was self-learning for me from the needs of the students. The one feedback from linguistics, I would say, is that the questions my students asked (while) learning Tamil forced me to find linguistic answers. So, I found that my linguistic training at that time was helpful to give a cogent explanation for certain structures and uses of Tamil. So I think you could say that that is kind of a trademark of my Tamil teaching: that I can explain each and every structure of Tamil with some linguistic theory behind that.

Nakassis: Since you mentioned Mysore, could you maybe tell me a little bit about where you went after you got your PhD at Chicago? And then I’m interested to hear also about how you came back to Chicago.

Annamalai: I got my PhD in 1969. Then I went to Central Institute of Indian Languages in Mysore in 1971. So, this Institute is a department of the Government of India; and the mandate of the Institute is the development of Indian languages; they defined it mostly in terms of developing Indian languages for use in education, which spanned from preliterate tribal languages to teaching major regional languages. So it was partly applied linguistics, which involved starting from devising a script for unwritten languages to preparing pedagogical material. There were two special needs. One was pedagogical materials in the regional languages for Indian students to learn them as a second language. So, until then, the States in India—which taught another language in the school system—used the textbooks of the state concerned, which are meant for mother-tongue students. So we were involved in preparing the second-language materials for Indian students, which is pedagogically quite different from teaching Americana because I can assume a lot of preexisting knowledge about the structures and cultures and things like that. But I would also say that my experience in Chicago to teach Tamil as a second language was helpful. At the Institute, I was not myself preparing the materials—and we did a lot of teacher training. But I had a team of researchers, and my job was to design the courses, preparing training, curriculum, and things like that. So my experience in Chicago was helpful in doing that. The other aspect of the Institute—”CIIL,” as it is called—is to help the maintenance of multilingualism in the country. So that involved, when it comes to tribal, or Indigenous languages, providing training for collection of folklore or even some training for doing creative writing by the tribal educated youth. And the other area is to make a study of the social functions of different languages in India; and we did it by conducting surveys in many parts of India. And this study of multilingualism as it is used on the ground in India was for the purpose of advising the Government of India to make policies about language. So, in that respect, I would say that CIIL was in a position of advising the government relating to language policies and also implementing the policies of the Government of India. So we had to wear two hats with regard to language policy and implementation. From sociolinguistics, the Institute moved also into other literacy programs preparing literacy primers in various languages, including Indigenous languages. So this is the overall spread of the work on the practical aspects of language work in India. To the question of how I made use of linguistics training here, as I mentioned earlier, I didn’t take any course—it was not available actually—in sociolinguistics or in language in culture and things like that which you teach now. So it was all self-learning and learning, so to say, by soiling your hands on the real field and facing problems and finding solutions. But my linguistics training was useful when we prepared grammars for the Indigenous languages; the linguistic training helped us to prepare grammars, which is more than a pedagogical (grammar) but is linguistically interesting.

Nakassis: Your PhD was a formal study of aspects of Tamil verbal morphology. When you were at CIIL, where were your academic interests? Did they go with the change in your work, or did you keep pursuing the same kinds of questions that you started answering at Chicago?

Annamalai: Yeah. See, I continue to work on syntax, and particularly on Tamil syntax, as far as my personal research goes—which actually required a lot of reading because Chomskyian linguistics was changing every year, so to say, so to keep up with developments was a challenge! And second, I have to read on the social aspects of language, that is, sociolinguistics, which was (done) on my own. So my research in that area is about two things. One is on language policy; in particular, (there) most of my research on the role of English is in education. And the other aspect is what is called language contact—that takes me to language history, how in a multilingual situation in India, contact between languages brings about grammatical changes. So, I kept my research interests and I was doing research in these three areas: the grammar of Tamil, language policy for a multilingual country, and the language changes due to contact. So that defined my academic area. It was tough in the sense that to keep your—( Before that, I should say that, as I said, I had the supervisory and mentoring and guiding work for my younger colleagues in the Central Institute of Indian Languages. If you are aware of how a government department works in India, you would realize that there is so much of paperwork and of pushing files. So my biggest task was to balance between that kind of administrative work because my title itself would show that I was called Professor-cum-Deputy Director). balance between professorial work and directing work was a big challenge! I’m happy that I survived that and got my academic interest and work reteined.

Nakassis: And then when did you transition to come back to the United States? First at Yale and then Chicago…

Annamalai: Towards the final year of Central Institute of Indian Languages, by which time I had become its Director, I had an invitation from the Institute of African and Asian Languages in the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. So I spent one year in Tokyo. According to the conditions of service of the government, I had to take early retirement to accept that invitation. So after I returned from Tokyo, I accepted opportunities to continue my research. I didn’t want to go back to any administrative work like the Vice Chancellor of a university or something like that. So the research opportunities came from universities abroad. So I spent six months at Leiden at the International Institute of Asian Studies. And then I taught for some time at the University of Melbourne, and a couple of other places. Then the invitation came from Yale University, which was thinking of starting a South Asian Studies Department. Yale, as you know, has Sanskrit from the earliest time. I think that’s the first university in this country which actually had first a teaching program in Sanskrit. But Yale University looked at Sanskrit as one of the Indo-European studies, not as a South Asian studies. So this was meant to be a shift to look at Sanskrit as an Indian language. And then it was thought at that time that they should expand it to Hindi and Tamil as modern languages. So I was invited to build a Tamil program at Yale University, which I did for five years.

Nakassis: And what year did you take your retirement from CIIL?

Annamalai: It was it was 1995 I think.

Nakassis: And then how did you end up back at where you got your PhD?

Annamalai: After I finished my contract at Yale University, Chicago University South Asian Department was looking for a person to replace Jim Lindholm, who was retiring for personal reasons. So when I was contacted, I jumped at that idea because it was like going back to my second home kind of thing. So, I accepted that invitation, which was initially for one year for the Department to find a regular replacement for Tamil instructor, but I stayed on for 11 years.

Nakassis: So that was 2009 or 2010?

Annamalai: Yeah, 2010, I think.

Nakassis: That was also the same year I came to the University.

Annamalai: Yeah.

Nakassis: And I’m curious to hear your impressions about what had changed.

You said you left in 1971 – so, 39 years later.

Annamalai: There are some important changes. You see, one is the South Asian Studies stabilized or took deeper roots here, not only the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilization (SALC) but also the interest in Tamil in sister departments like history, anthropology, political science, and others continued. So I find broader interest in Tamil studies; and that is reflected in my Tamil teaching also, in terms of the student backgrounds. I get students who would like to do graduate work in South Asian studies, or graduate work in any of the social sciences or humanities or religious studies. So that means that in the second innings, I have expanded from teaching colloquial Tamil to teaching some Tamil texts; not necessarily literary texts alone, but also the text of traditional grammars and sometimes inscriptions and the different kinds of literary texts. Since the students from various departments come to learn Tamil for their own interests, the text selection was open ended in the sense that it’s not that I like one text so I will teach it and students would come and learn that text. I made it open ended so whatever text the student wants they could learn it. I would be able to crack it, even though I have never seen that text in my academic life. Another major change I noticed is the status of Instructor—now it’s called Instructional Professor—has changed. When I was there in the sixties, I wouldn’t be a part of the departmental of meetings or COSAS meetings and things like that. They (those meetings) were out of the domain or reach of lecturers. Here, I would see that language teaching has gained some status within the South Asian Studies. This I would say is a major structural change.

In my personal life, the major change is my shift to, I could say, South Asian studies in the sense of reading more and more Tamil literary texts and also reading about multidisciplinary research on South Asian Studies study. As I said, I started with Masters in Tamil, and then I was attracted by the new lady Linguistics coming in. Then my attention was on linguistics. Even when I worked on Tamil, it would be on the grammar of Tamil, or interpreting traditional grammatical works, et cetera. The Tamil literature was primarily my personal reading interest. I never taught Tamil literature as such. So it is a gap of about 39 years, right? I came back and then I chose to teach not only the colloquial and modern language to students, but also the pre-modern Tamil texts to the advanced students. That was challenging in its own way, not only because of the gap in my personal nature of acquaintance with Tamil literature—I mean, I had personal acquaintance but not academic interaction with Tamil texts. But the other challenge was—which is similar to the challenge I had to Mysore, (where) I had to learn on my own the sociolinguistics and things like that in CIIL; so when I came back here the second time, I found that the research on South Asia has grown enormously and I was totally unaware of that when I was focusing only on linguistics. So, I had to read up to what you people in anthropology, or sociology, or political science, or even the people in the SALC department, write about Tamil or write about the other Indian languages. That was, again, a gap which I had to match when I came here.

Nakassis: I want to ask about your experience in Tamil Nadu in the sixties, but before I get to that, your BA and your MA was in Tamil and-

Annamalai: No, my BA was in mathematics.

Nakassis: Mathematics, right. But your MA was in Tamil. And so you would have had some exposure to being taught, in addition to linguistics, Tamil literature. So, after a whole career of focusing on Tamil syntax, morphology, sociolinguistics, teaching the colloquial language, language politics, policy, and then in your second innings, coming back and turning back actually to some of the topics that you would have been taught, and maybe even some of the texts that you would have been taught when you were just in your early twenties, what was that experience like coming full circle, now not as a student, but as a teacher of literature?

Annamalai: Yeah, I would put it this way: I didn’t lose interest in literature. As a Tamil speaker, I have been reading modern literature as well as some of the pre-modern literature. But teaching it is an entirely different ballgame, as you know. So, when I faced that challenge, to my happiness I found that I didn’t find it intimidating. I didn’t find that it’s a task unfamiliar to me. I told myself that I’m a Tamil speaker, I’m a linguist, so I should be able to crack any text which is placed before me. I think I successfully did that. If you see the list of Tamil texts we read in the classes, it’s a wide range of range of texts. So that was not a problem. The problem was, as I said earlier, to put the readings in a theoretical context, I don’t know what Costas (Nakassis) says or what other social scientists say about a particular subject or the theme which the literary texts deal with. That was a learning curve, but it was a challenging experience. So what I find is, because I took up the challenge, I’m running a little behind in reading up on Chomskyian linguistics.

Nakassis: Well, I mean, of course, linguistics has changed, too.

Annamalai: Yeah, right, so catching up in multiple fields is an impossible task!

Nakassis: Did that kind of teaching, you know, going back and teaching anything from Tolkaappiyam to Dutch grammars from the 18th and 19th century to texts coming from Muslim communities, I mean the wide variety of texts you’ve taught as a Tamil speaker, or as a scholar of Tamil, did that kind of experience change your view on language, on the Tamil language?

Annamalai: Certainly it did. The change did not start from here. It had already started before I came to Chicago. It [what changed] is the nationalistic view that Tamil grew or developed in isolation, isolation of other languages and literature. So the perspective which I gained and not set after coming to Chicago the second time, is how I sould look at Tamil in relation to the totality of Indian languages and Indian literature. And I learned the methods of looking at a text from other disciplines. So, it was a shift from linguistic philology, or verbal analysis to cultural; all kinds of methodological shifts are also to be taken when I started reading a text. The important thing, as I said, is that I found them all enjoyable. So that’s why my stay here is enjoyable. It’s not that I had to teach a text because I had to teach it, right? So, one reason for the happiness probably was that the University of Chicago students were also very stimulating. So I got good feedback.

Nakassis: You mentioned the idea, the ideology, the kind of conception about Tamil is a language that grew up in isolation. And I always associated that with, of course, a particular political movement that starts in the late 19th century and really gains steam in the 20th century, and becomes at a time what we now call the Dravidian movement and what was called at the time the Dravidian movement. The Dravidian movement touched every aspect of life in Tamil Nadu, which is your home state, and the Dravidian parties came into power in your generation; and indeed, many of the major political protests, in some ways, the major political protest happened at your university, Annamalai University in the sixties when you were there. So, I’m kind of curious now, after your long, illustrious career, taking so many different points of view on the Tamil language and taught Tamil in so many different places, to diaspora students, to heritage students, to students in India, I’m curious about, looking back, what you now see as maybe the impact of that form of Dravidian thought on your own thinking, in your own scholarship, because it must have been such a powerful moment at the time when you were just starting.

Annamalai: Yeah, it was a powerful moment in my student life. As you said, the Dravidian ideology, or Tamil nationalism, was a dominating ideology. I myself have participated in, and taking the Tamil education of, that time. When I came to Annamalai University T. P. Meenakshisundaram joined as the new head of the Tamil Department. But the student body was wedded to the Dravidian ideology. So I could see the tension in the class about the interpretation of a Tamil texts and also how you approach the study of Tamil. So, I would say that I learned something from T. P. Meenakshisundaram about how you can look at Tamil in a broader context. That’s one. And also how you can look at Tamil in a purely objective way. I think that stays on with me in from those times. But that tension was there. And then when I went to Karnataka to work at the Central Institute of Languages, I got exposed to the whole of India, beyond Tamil Nadu. I realized very quickly that if I loved Tamil and will do anything for Tamil, the same sentiment was expressed with my Kannada colleagues:” I love Kannada, I will do anything for Kannada”. Then the question came up why Tamil is different. Everybody has their own relationship with their language. So, I realized that the relationship with one’s language is much more shared or widespread. And that also took me to see how I can look at Tamil from the perspective of other language communities. And then when I came back to Chicago, as I said, it is looking at the Indian languages and cultures as a kind of networking phenomenon rather than conflicting or competing entities between themselves. So, this view is still not accepted widely among the Tamil scholars in India, so there is rejection of my views from– I would call it broadly of the view about Tamil- not only about the present-day Tamil, but also the whole history of Tamil.

Nakassis: Have you seen a change in the reception of your work? Your work has been, I think, rightly very critical of some of the purest kind of politics.

Annamalai: Yeah. See, what I find is, as I tell my critical friends, that I had one advantage, which they don’t have, namely, I lived much of my academic adult life outside Tamil Nadu; in Karnataka, and then in the US. So I could have a distanced view about Tamil, a bird’s eye view, if you want to call it that. So I tell them that that makes a change about the view of Tamil. Even though there is a critical rejection of my perspective about Tamil, so far I don’t see any personal animosity against me. I think there’s a general acceptance of my scholarship and also my positions as a director and as a visiting professor and things like that help-they increass the acceptability. And I think there’s a general view among the Tamil scholars that I am not holding these views for granting any political acts, or that I do it for political games and things like that. So, the acceptance is there. I find the acceptance more among the younger generation than the older generation, so I hope that it will spread. It’s from this point a few recently, as you know, I gave interviews to Jawaharlal Nehru University faculty and students spelling out my perspectives on Tamil. So I would like to see what impact to have.

Nakassis: The generation where you came up, it’s interesting because there was such an explosion of linguistics in India in the sixties and the seventies, and also the institutionalization of a certain kind of language politics in the state (of Tamil Nadu) at the same time. Looking back, as both as someone who participated in that moment but also as a professional linguist, I’m curious on your thoughts about the contemporary moment and maybe what the future might look like for Tamil language, Tamil language politics, because we’re at a very interesting different moment in the history of the Dravidian movement, but also in many ways, the history of linguistics; as we were kind of hinting at, Chomsky dominated so much of the second half of the 20th century of linguistics and obviously is still important in the same way that Dravidianism, of course, is still important in Tamil Nadu. But among the younger generations of linguists and other social scientists and sounds like also Tamil scholars, maybe there’s different kind of vision or maybe a different horizon looming.

Annamalai: I think still the tension is there; as you rightly said, that when linguistics was introduced to the Tamil academic world, it was embraced as giving a fresh light to understand Tamil grammar. At the same time, there were also resistance, which comes from what broadly could be called the Dravidian ideology or Tamil nationalist ideology, (which) is that there is nothing new to learn in Tamil regarding grammar. So the Tamil grammar has already been done for life by Tolkappiyam and things like that. So there was a view that people like me were talking Tamil grammar of the Tamil tradition in English, and that’s the only difference. So that view still prevails in the Tamil academic world. But I see some changes, which asked the questions like what has been done to Tamil besides getting political recognition and getting even some political power. What is the contribution of the ideology to Tamil? One contribution is the establishment of the classicalness of Tamil and also the antiquity of Tamil. So it is still strong not only in the popular mind but also in the academic, scholarly mind. But I think my sense is that people are asking new questions about this. But having said this, I would say that the getting enamored about the past of Tamil rather than the future of Tamil is still strong.

Nakassis: And what would you say about what you think the major topics for Tamil studies, Tamil research should be looking forward?

Annamalai: See, my question, which I suggest to students who want to pursue new avenues is this: the larger question is that Tamil survived as literary language, as a living language, for more than two thousand years. So you should examine how and why, rather than just feeling proud about that. Yeah, it is a fact to be proud of, but you should also ask why it happened Tamil and other languages like Latin, for example, did not survive to be a modern literary language. So that would give you an idea of the inner strength of Tamil. And to find the inner strength I have been telling them that they should move away from the one-point analysis that anything about Tamil could be and should be only done in relation to Sanskrit. Whether Sanskrit did good or bad that’s the dominating question. So they’ll have to move beyond that and ask about the inner strength of Tamil. Under that larger question, the other things, like Tamil’s relationship with other languages and literatures, and Tamil’s inventiveness in creativity and all those things would be addressed. So, my major concern, a major suggestion to the younger scholars, is that they should move away from visualizing that the duty of Tamil scholarship, not only of political activists, but also of Tamil scholarship, is to protect Tamil. So they should move from that kind of mindset to how you increase the creativity of Tamil, not only in literature, but in other areas of knowledge. I think that should be the fulcrum of a paradigm change about Tamil research, which I hope it will take place.

Nakassis: As you said once to me, the Tamil language is like clay.

Annamalai: Yes. I strongly believe in that, because the current view of shaping Tamil is like this: it is already shaped like the Lord Ganesha, and you fall at his feet and get his blessing, rather than that they should look at Tamil also as a raw clay and make many more dolls which are never thought of before. But that is a difficult concept to sell.

Nakassis: Especially because there’s such a political investment. But also, as you said, because the narrative has for a longtime been to protect Tamil. And I think the worry is the worry of losing the language somehow.

Annamalai: Yeah, right. So what happens by this kind of attitude is , as I wrote in one of my Tamil essays, that you love your mother and you buy all ornaments for her, but you starve her, right? And this is not loving your mother. This should not happen to language, right? You should do something to the language. So the equation, if I can use a Tamil phrase, Tamil kāval is not Tamil kātal (‘Protecting Tamil is not loving Tamil’). These are two different things.

Nakassis: Well, I mean, one of the great ironies, of course, as you pointed out in your sociolinguistics work, is that a focus on the purity of Tamil—and in particular with respect to Sanskrit and Hindi—went alongside of a deep kind of connection between English and in a certain kind of relationship to the Tamil language. And it’s interesting to think that one of the, mayb,e by products of the Dravidian movement was an even deeper connection between English and the Tamil language. And part of that, as you’ve also pointed out, has to do with the political economy of language; and just thinking about where Tamil studies is today, students will oftentimes much more prefer to go into things like Business Administration or Engineering (degrees). And I think it’s a major kind of question for Tamil studies about how to encourage interest in studying the language.

Annamalai: I mean this is the biggest problem, right? Why Tamils, from ordinary to scholarly, would think that Tamil is an asset in which they have a part. But at the same time, they also believe very sincerely that Tamil is a liability. So they don’t want to pass on the liability to their children and that’s why English comes in, to offset the supposed liability. But they also would like to treat Tamil as an heirloom that they pass on to their children, right? So they don’t abandon that either. That’s why you have this dichotomy of a relationship with Tamil. With English, the larger question, I would say, is that in the earlier times, Tamil dealt with a cosmopolitan language, Sanskrit, in certain ways. Now the question is, how will it deal with the new cosmopolitan language, English, right? So it’s not simply a matter of spoiling Tamil, or as somebody said that the oan words are all pockmarks on Tamil. But I think we had to ask the question of how Tamil would deal with the cosmopolitan languages as it deals with the other languages. So, as you said, that the great contribution of Dravidian ideology is the political consciousness about Tamil and the political power it gave to Tamil speakers. This has to be converted into creative energies. Now the creative energy is restricted to modern literature, fiction and poetry, and this is outside the Dravidian ideology, that is, whatever is created. It doesn’t extend to science in the broader sense, soft science and hard science and all kinds of knowledge systems. So, my sense is the Tamil speakers as well as scholars—I mean, scholars, those who specialize in Tamil language literature, but also Tamil speakers who specialize in different knowledge systems—how they could bring the creative potential of Tamil out. So, I gave one slogan in one of the meetings; in English it’s: “Tamil doesn’t want your uyir, your life, but it wants your aRivu,your mind, your knowledge.” So the political attitude has to change, right? So that would make Tamil a modern language, and that would go a few steps in eradicating the idea of Tamil being a liability.

Nakassis: I just want to ask one more question. A scholar like you doesn’t retire. In fact, in a sense, you’ve already retired from one career and started again, a second career as an academic. And I know that you’re retiring from the University of Chicago, but you’re not retiring as a scholar. So I just wanted to hear a little bit about what you plan on doing?

Annamalai: Yeah. So, I should say that I’m lucky that I still have an active mind in my eighth decade of life, so I hope to keep I goingt. When I look back, I find that I compare myself more like a short-story writer in the sense that I have written many papers. I was never a novelist. I didn’t write book-length studies in the earlier years. So I will focus on writing first. And probably I will write longer pieces than journal articles. And to start with, I am thinking of collecting some of my published papers and organize them into different themes and publish them into collected papers with cohesion . And also, there has been a long-time demand on me to write a grammar of modern Tamil. That’s a big challenge that I want to take up, but I should see how my mind cooperates! That would be a major obligation for my linguistics friends. The other demand is from nonlinguistic friends, who belong to what we call the intelligentsia, which is that I write my ideas of what Tamil is, how it started and where it is going. That kind of epistemological way of presenting what the Tamil language is. That’s a demand to take away the emotional approach to Tamil and make it, to the extent possible, a kind of intellectual reformulation of Tamil. I hope I’ll be able to do these things.

Nakassis: I think you will. And we’re all eager to see the publications and get a chance to read them. So thank you so much. This has been so great.

Annamalai: Thank you very much.

Nakassis: We could talk, I’m sure, for another hour.

Annamalai: I love to talk also, because I want to share some ideas. I’m happy that you asked these questions. I was able to go back in my memory lane and see what I did, and why I did them and things like that.

NB: the text of the conversation has been emended for readability and to correct certain errata